Today, inequality is high on the international agenda. After the hype on poverty – Millennium Development Goals -, U.N. organisations and the Bretton Woods institutions play a major role in producing and distributing knowledge on the different dimensions of inequality and on how it is shaping today’s world and its perspectives on development.

In this contribution, I want to examine what knowledge these institutions create and disseminate about ‘inequality’ and how this knowledge has evolved since their inception – the end of the Second World War and the start of a decolonisation process with an associated development project.

The methodology used for this research is based on Michel Foucault’s concept of discourse (Foucault, 1972) and starts from the statements in major documents on inequality from 2000 to 2020, the way they can be understood and how they can be explained.

This involves deconstructing and reconstructing various documents, bringing out the intertextuality, exposing the continuities and discontinuities between them and looking for the ‘order of discourse’ – that is, the definition of a field of knowledge -, and for a ‘dispositif’ of knowledge and power.

In this respect, inequality must be seen as a discursive and social construction that can have an influence on reality – but does not coincide with it, in the same way as perceptions of inequality do not coincide with its reality – and on the policies that are, or are not, being devised to fight inequality. This research, then, is not about the material reality of inequality, but about what is said and written about it from a perspective of a sociology of knowledge. It does not deal with policies nor with the contextualisation of the accumulated knowledge, but only with the knowledge itself. It goes without saying that this knowledge does not stand alone, but has, in recent decades, been confronted with alternative narratives such as those of post-development and world systems analysis.

Such a discourse analysis is important because it shows how major actors think about a certain problem at a global level, which policy this can give rise to at a national level and what responses it can – or cannot – lead to.

I start with a reflection on the definition of inequality, a multidimensional phenomenon that embarks all aspects of life though the one dimension that is leading to most reactions and even indignation is inequality of wealth and incomes. In the second part I look at the history of inequality in the global development discourse, first theories having been based on the ‘gap’ between ‘industrialised’ countries and ‘underdeveloped’ ones. In part three I look at the emergence of the poverty issue and how it changed the development discourse, more particularly all thinking on social development. Part four concerns the questions and doubts around this poverty focus and how it opened the new horizon for an inequality discourse. Point five analyses and tries to explain the new thinking on inequality, showing how UN organisations and the Bretton Woods institutions follow divergent paths. Point six briefly looks at the numbers. In the conclusion, I summarize the findings and conclude with a final – and political – reflection.

For more details on methodology, I refer to Mestrum (2022).

- What is inequality?

The search for a definition immediately reveals the problem. Inequality has an incredibly broad meaning – from material inequality to inequality of opportunity with a wide range of possibilities within each category.

In a recent sociological study (Dubet, 2022), the author explains how we have evolved from first a caste system – in which inequalities were seen as ‘natural’ and therefore unchangeable – to a class system – in which people and societies are approached as a destiny and community of values. Today, however, Dubet continues, inequalities are individualised. We are all ‘unequal’, as black people, as women, as migrants, as disabled people, and so on. We have all become ‘intersectional’, as it were, and in such a world it is not easy to devise solidarity systems. For this must be made clear: inequality only gets attention when it is considered too great and/or too unjust. The problem cannot be separated from the ‘equality’ of all people, a vision that was introduced with Western modernity. Inequality is studied as soon as it is judged that it may have consequences for policy areas such as social integration or the economy. The solution will then be sought in those policy areas that one wants or is able to change.

Yet, the most visible inequality that immediately leads to the greatest indignation remains the material inequality of incomes and assets. But of whom? Of countries? Of people? And what do you wish to measure? Inequality between countries, within countries or globally, without borders? Relative (in percentage) or absolute? Gross or net (taking into account taxes and benefits)? And what do you measure for individuals and for households? Consumption or income?

For inequality of opportunity, the range is even wider. You can measure just about anything: gender inequality, opportunities for education, for housing, for access to rights, for vaccines, inequality in consumption, in life expectancy, etc.

This study will look in particular at what international institutions deal with, what aspects they attach the most importance to, because this will tell us something about how they see inequality and possibly want to tackle.

This research starts with an overview of the past history and continues with and analysis of the documents published by the U.N., its subsidiaries and the Bretton Woods institutions since the beginning of the 21st century, when inequality came on the international agenda, and until 2020.

- The Gap

When, especially at the U.N., the first theories of development emerged, they started from what was seen as a major problem: the ‘gap’ between developed and ‘underdeveloped’ countries, or in other words the inequality between countries. This gap was attributed to the ‘backwardness’ of the decolonised countries.

Although various alternative theories were developed before decolonisation – think of the divergent theses on an African socialism – there was a large consensus between North and South on this gap. This can be clearly seen in the four UN resolutions on the ‘Decades for Development’ (United Nations, 1961, 1970, 1980, 1990), which repeatedly mention ‘the gap’ that is constantly widening instead of narrowing. This is seen as unacceptable because it threatens the fundamental goals of the U.N.: peace and international security. In 1990, it states that the goal has not been achieved and that policies must be fundamentally adjusted.

The UN resolution on social progress (United Nations, 1969) repeats this same mantra and refers to the necessary solidarity and also to an equitable distribution of national income.

In 1969, World Bank President McNamara commissioned a study on the results of twenty years of ‘aid’. The Pearson report (Pearson, 1969) also speaks of a ‘growing gap’. But it also states that it cannot be the intention to eliminate all inequality. The report does see a ‘moral obligation’ to reduce disparities and inequities in order to avoid ending up in a world of those who have and those who have not.

From the 1970s onwards, a slight shift begins to emerge, for which there are various explanations.

It is worth remembering that in its early years, the U.N. never spoke of ‘poverty’. There were regular reports on the social situation in the countries of the South, mentioning the lack of education, health care, housing and so on. The solution to this was ‘development’, in the sense given to it in the many U.N. resolutions. The World Bank, for its part, initially did not want to support any social project. (Kapur et al., 1997).

The International Labour Organisation (ILO), launched a global employment programme in 1969, because it had become acquainted with the informal sector and the working poor in Kenya. The emphasis is increasingly on equity, basic needs and equal opportunities (ILO, 1976).

With researchers such as Tinbergen, Singer, Myrdal, Seers and Ul Haq, the emphasis is more and more on social development. At the U.N., a ‘unified approach‘ is sought in which economic and social development can be integrated into one concept (Arndt, 1987).

In the South, people did not like the idea. After the Bandung Conference (1956), the success of the Cuban revolution (1959), the papal encyclical Populorum Progressio (1967) and the movements around May 1968, people continued to insist on a worldwide redistribution of income. The aim was a different economic order and more equality in the ‘community of nations’, not international interference in internal policy (Arndt, 1987).

Hence the U.N. resolutions on a new international economic order (United Nations, 1974) and on the ‘economic rights and duties’ of nations (United Nations, 1974b), which note that the gap continues to widen and that inequalities and injustices must be eliminated. This is the purpose of development and of international economic cooperation, and this is how peace and international security can be maintained. The third UNCTAD (Organisation for Trade and Development) conference in Santiago de Chile in 1972 also pointed out the very poor distribution of incomes.

Nevertheless, the shift towards social development and poverty continues, partly under pressure from the World Bank. A new report is commissioned on ‘redistribution with growth’ (Chenery et al.,1974) and it indicates exactly what the authors are concerned about. People are prepared to think about a better distribution of income, but without endangering growth. This is only possible, they say, if it is not the results of growth that are redistributed but growth itself, or in other words, it is the incomes of the poorest groups that have to grow. And this can be done, not so much with transfers of tax revenue, but with public investment, targeting, growth and family planning. In other words, growth is central and necessary in order to avoid redistribution. It is the productivity of poor people that must be increased.

This is a decisive step towards inequality within countries rather than between them, and poverty becomes a central issue.

This is clearly reflected in the speeches of World Bank President McNamara at the annual meetings of the Bretton Woods institutions. ‘The wealth of rich countries does not have to be reduced to help poor countries, they are only asked to give up a small percentage of their growing wealth‘ (McNamara, 1972). ‘The fundamental problem of poverty and growth in the developing world is very simple. Growth does not reach the poor and the poor do not really contribute to growth‘ (McNamara, 1973). As a logical consequence, the World Bank began to focus on rural development (World Bank, 1975), but at the time still assumed that social protection was needed to take poor people out of their tribal bonds and bring them into modernity as autonomous market players.

The focus on poverty was a logical consequence of the shift from income inequality between countries to income inequality within countries, and of the political choice to remedy inequality by raising growth among poor people.

This poverty programme was not long-lived. The cancellation by the U.S. of the Bretton Woods rules in 1971, the oil crisis and the ensuing foreign debt crisis in the South thoroughly shook up the agenda.

With the crisis of external debt began a long period of ‘structural adjustment’ and the ‘Washington Consensus’ (Williamson, 1990), imposed by the IMF and the World Bank. This amounts to fiscal discipline, restructuring of public expenditure, tax reform, financial and trade liberalisation, privatisation and deregulation and protection of property rights. This will eventually lead to the abandonment of the development narrative and the introduction of a ‘pensée unique’, called neoliberalism (Mestrum, 2002).

Very quickly, however, there were serious complaints about the social. .consequences of these ‘structural adjustments’, initially from within the U.N. family, such as from Unicef, which advocated ‘adjustment with a human face’ (Cornia, 1987; Unicef, 1989).

- Poverty

1990 brings a new turning point. The World Bank publishes its first major poverty report (World Bank, 1990) and UNDP (UN Development Programme) its first report on ‘human development’ (UNDP, 1990). Reactions to this in the developing world are generally very positive, because it gives the impression that there is finally a desire to tackle the disastrous social consequences of ‘structural adjustment’. However, this is not the objective of the World Bank, as it believes structural adjustment is necessary and even crucial to fight poverty. Measures that prevent markets from functioning properly do not benefit the poor, it argues (World Bank, 1993).

What is striking is that, at the time of this first poverty report, the Bank had absolutely no statistics to support its new priority. Secondly, it is important to note that, contrary to the early seventies, social security is no longer seen as a step towards modernity and development. In the new approach, poverty policies replace social security in order to make poor people feel the necessary pressure and to make non-poor people look after themselves. Inequality, finally, disappears completely from view. ‘Poverty is not inequality‘ (World Bank, 1990: 3) and the World Bank only looks at absolute and not relative poverty. It admits that there is no question of global convergence (World Bank, 1995: 9), that the relationship between poverty and inequality is rather complex, that redistribution can hinder growth, that too much inequality can do so as well, and that a market economy does, after all, need a certain degree of inequality (World Bank, 1990: 162; World Bank, 1995: 122; World Bank, 1996: xii, 6, 32).

For its part, UNDP emphasises the policies that can be pursued. It calculates an index of human development with life expectancy, infant mortality and literacy rates added to the Gross Domestic Product and thus arrives at a completely different ranking of countries. Where a socialist or social-democratic policy is pursued, countries, thanks to their social achievements, move up the list, while rich oil-producing countries such as those in the Middle East fall down the stairs. The message is inspired by A.K. Sen (Sen, 1992) and human development is about giving people choices. Policy can make a huge difference in making this happen.

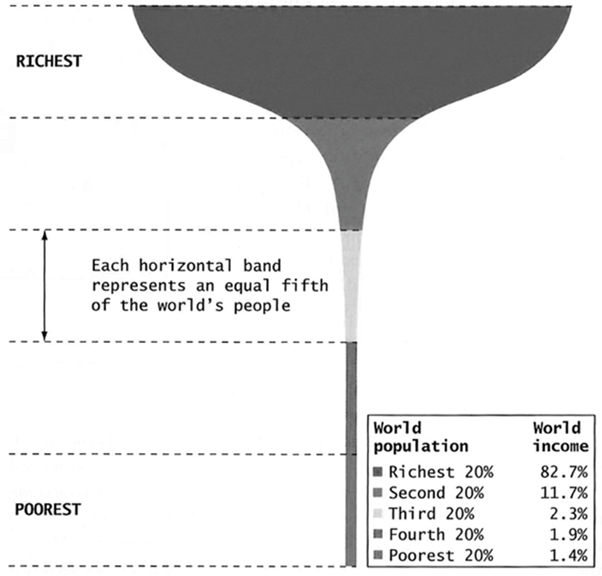

At UNDP, inequality is high on the agenda, with the famous glass of champagne of 1992 (see point 6), although no concrete solutions are linked to it and the focus is on equality of opportunity.

One of the important features of this new discourse is that it completely shifts the focus from countries to people and approaches these people as equals in one world with one humanity. Unfortunately, some of these people are poor because they have not been able to contribute to development and growth. It is governments that deprive people of their opportunities to make that equality a reality – through discrimination, restrictions on access to markets, labour market protection… – but in the long run all differences should be eliminated, except for income differences as will be shown. All human beings are called to become autonomous and to take care of themselves. Poor people are homines oeconomici in the making.

This shift was prepared in a 1986 United Nations resolution on the right to development, henceforth a human right that is interpreted more individually than collectively. In this way, the emphasis is on equality of opportunity and income inequality is not seen as a problem.

The entire decade of the 1990s has seen a tremendous amount of attention paid to poverty and especially its measurement. Poverty is a central issue in all international institutions and at all global U.N. conferences. In 2000, the ‘Millennium Summit’ at the U.N. adopted a resolution with ‘millennium development goals’, the first of which is the reduction by half of extreme poverty by 2015 (at that time an income of less than one USD per day) (United Nations, 1990).

- Questions and doubts

The great success of this poverty discourse eventually led to many questions, criticisms and a shift towards inequality, a topic that is experiencing a real boom today.

In 2000, the World Bank published its second major poverty report (World Bank, 2000), which was prepared very thoroughly. A large-scale participatory poverty study was carried out (Narayan et al., 2000) and a whole series of papers on inequality appeared with questions from economic theory. Kanbur & Lustig (1999), for instance, wonder why the theme is once again on the agenda. Income distribution, they argue, is an integral part of a country’s economic success or failure. Inequality may not change that easily in the long run, but Kuznets (the economist of the inverted U-curve, which means that after an initial rising phase, inequality starts to decline) was wrong. Inequality and growth are closely linked and it goes without saying that education policy, for example, can play a major role. This sets the tone.

But in a remarkable work published in 2004, Cornia points out that inequality may well be incompatible with the goal of poverty reduction through growth, precisely because growth is slowed down by that inequality (Cornia, 2004).

The World Bank’s own second poverty report devotes a chapter to growth, inequality and poverty (World Bank, 2000: 45). Throughout this report, it becomes clear that doubts are setting in: it is about a ‘complex set of interactions‘ (World Bank, 2000: 45), ‘no systematic link between growth and income inequality‘ (World Bank, 2000: 52) …. ‘One can find evidence for‘ … ‘some policies‘ … ‘sometimes research shows‘ … ‘policies to improve the distribution of incomes and assets can have a double effect‘ … ‘sometimes there are win win opportunities’ (World Bank, 2000: 56)… ‘Reforms are sometimes to the advantage, sometimes to the disadvantage of poor people…’ (World Bank, 2000: 67).

In the same report, a new framework for ‘risk management’ is proposed (World Bank, 2000: 141), previously called a ‘new framework for social protection’ by the World Bank’s research department (Holzmann & Jørgensen, 1999). The World Bank has thus done away with ‘social security’ as an insurance mechanism as proposed by the International Labour Organisation since 1952 (ILO, 1952). Risk management largely ignores social and economic rights and responds to a completely different logic.

In short, while the World Bank wants to limit itself to poverty reduction, translate social security into a new concept of social protection with risk management (Mestrum, 2019), it is forced to face the fact that it cannot overlook inequality, especially to achieve that one big goal of growth. Too much inequality can hinder growth. This is demonstrated by its own research department (Ravallion, 2001). The World Bank’s doubts also have to do with a lack of empirical data on the relationship between growth and distributive change. Without such data, it is difficult to give policy advice to its clients. Do the poor benefit from growth? Does globalisation increase income inequality? More equality is good for growth and growth can reduce poverty, concludes Ravallion (2001).

Moreover, a great deal of research has been carried out in this period into the relationship between growth and inequality (Cingano, 2014) and the impact of globalisation on inequality in the world. However, a lack of data and the many different methodologies make it difficult to draw firm conclusions (Ravallion, 2004; Mestrum, 2009).

From this period onwards, it is clear that the topic of inequality can no longer be hidden behind the humanitarian view of poverty. From the beginning of the 21ste century, a stream of research is being launched and the UN institutions themselves are proving particularly active.

- Inequality in focus

What follows looks in more detail at the documents published by the U.N., its subsidiaries and the Bretton Woods institutions on inequality since the beginning of this century and until 2020 (for a list of the analysed documents and how they can be understood I refer to Mestrum (2022). Documents were analysed on the basis of five questions:

- Which inequalities are under scrutiny?

- What is the current situation?

- Why does one need to reduce inequality?

- What connection is mentioned with poverty and/or with (sustainable) development?

- How does one plan to reduce inequality?

What follows are some elements of explanation.

5.1. No consensus

What emerges clearly from the discourse analysis is that there is no global consensus on the approach to inequality and no unique field of knowledge. The debate is still evolving with a certain continuity at the World Bank and a discontinuity at the U.N. questioning the exclusive poverty focus. Because of the many possibilities, there is also no clear overview of data, although the various institutions do provide sufficient figures to get an idea of how great inequality is in its various dimensions.

When the agenda for poverty reduction was introduced in 1990, a consensus between the international organisations was reached very quickly. Poverty is indeed a consensus topic par excellence and, even if there are different ideological visions behind it, it is easy to reach an agreement on fighting it. In practice, this international poverty reduction has become part of a neo-liberal agenda and it is against this that various U.N. organisations have reacted quite rapidly by focusing on inequality.

Inequality is anything but a consensual issue, and several World Bank papers keep repeating that every market economy needs some degree of inequality. After all, the liberal thesis has always been that as long as everyone improves, there is no problem with inequality (Economist, 2001). Branco Milanovic, who worked for the World Bank for a long time, disproves this proposition (Milanovic, 2003) in an article with numerous examples of how people’s sense of justice can be hurt by too much inequality. No individual is an island or lives on an island, which implies that everyone’s well-being is determined by the well-being – and income – of others. That inequality is experienced as a ‘sensitive topic’ – even in communist regimes, as Milanovic experienced before his work in the West – has to do with the fact that seeing poverty and misery speaks to the conscience of rich people, but ‘ordinary’ inequality does not. Poverty policy is a painkiller for the bad conscience of the rich, Milanovic says. ‘Poverty policy is the price that the rich are willing to pay so that their own incomes are not affected’ (Milanovic, 2003).

No one argues that inequality is decreasing and that we are clearly going in the right direction. Nevertheless, the different approaches correspond to ideological differences that are more difficult to hide around inequality than around poverty. The World Bank sticks to its neo-liberal policy of addressing inequality only marginally, because it can jeopardise both growth and poverty reduction. Redistribution is never the real goal, though this is certainly the case at the U.N., where the policy mantras of 1990 are being challenged. In this sense, the World Bank sticks to its old symbolic universe, while the U.N. tries to return to the pre-poverty and pro-development era.

There is consensus, however, that it is not only incomes that count, but also equality of opportunity, especially in terms of education and health care.

- World Bank and U.N. are not in the lead

Unlike the poverty issue, which was not on the international agenda before 1990, the inequality discourse is not the result of an initiative by the global institutions. The World Bank, even more than the U.N. institutions, follows the research done by more and more researchers around the world. At the World Bank, this is not done wholeheartedly. The U.N. gratefully uses that research to support its criticism of ‘structural adjustment’ and poverty policy. Inequality came on the international agenda thanks to the research work in academia and the research departments of the institutions themselves, not at the request of those institutions (Mestrum, 2009).

- All forms of inequality are addressed

All possible forms of inequality are discussed in the various documents, often without clarification as to what exactly is meant. This multiplicity of approaches and measurements suits the World Bank well, since in this way no explicit choice needs to be made.

- Don’t look up!

In fact, there is a great deal of continuity at the World Bank. What was already stated in Chenery’s work in 1974 (Chenery et al., 1974) is repeated today. Inequality within countries must be reduced by raising the incomes of those at the bottom. In this way, as in the fight against poverty, social policies can be implemented that do not affect the incomes of the top. Don’t look up! And, of course, the incomes at the bottom will never be raised so much that they come close to the top.

Taxation, widely recognised as the tool of choice for capping incomes at the top, is only sparsely acknowledged at the World Bank. One cannot totally ignore it, but it is constantly repeated that taxes can slow down growth and that caution is therefore called for. Redistribution of incomes is not on the agenda.

The same applies to allowances. Of course they can help, but they should not benefit people who do not really need them. A recent book (Grosh et al., 2022) also indicates methods to be able to ‘target’ even better and even more precisely, while there is a whole literature questioning their effectiveness (Kidd & Athias, 2019). But as was already established in the early poverty discourse, the World Bank still believes that income should not come first (Mestrum, 2002).

- The U.N. against the Washington Consensus

Among the various U.N. institutions, the tone is entirely different. There is, in the first instance, especially at the Institute for Research on Social Development (UNRISD) and in the reports on the social situation in the world, implicit and explicit criticism of poverty policies. The U.N. agenda, built up through the many global conferences of the 1990s, does indeed go far beyond poverty reduction. The best example is the 1995 UN Conference on ‘Social Development’ (United Nations, 1995). It contains three equally important chapters: poverty, employment, and social integration. With the adoption of the Millennium Goals in 2000, this was very much watered down. With UNRISD, the criticism is somewhat more implicit, but not to be misunderstood.

Neo-liberal globalisation policies are also discussed in various U.N. documents, including the trade policies of the WTO. The poverty reduction documents of the 1990s clearly did not include any changes to the ‘Washington Consensus’. The great ‘renewal’, led by President Wolfensohn at the World Bank, with Joe Stiglitz at the head of the economic department (World Bank, 1996) did in fact consist of no more than a readjustment of the order of the various reforms. To this day, the World Bank and IMF continue to demand cuts that severely inhibit social development (Ortiz & Cummins, 2021).

- Equality and justice

For all institutions, economic growth is mentioned as a goal to be achieved and inequality is that what hinders this growth. In the case of the World Bank, this, together with possible social conflicts, is the main reason for tackling inequality.

At the UN and its various subsidiary organisations, growth is one of many other objectives. The UN continues to defend its development agenda, today contained in the Sustainable Development Goals, but with a clear section on social development and the implementation of social protection systems.

For the World Bank and the IMF, it matters to reduce inequality to a level that allows growth to continue unimpeded and no one feels treated unfairly. No one can, of course, specify what a ‘just’ level of inequality might be. Even with human development and a top level, this is, ‘equality’ in terms of life expectancy, literacy, infant mortality and so on, incomes may still be so far apart that they do indeed lead to social protest.

- What is not talked about

Finally, it is also important to point out what the various documents do not discuss: where the great inequality comes from, the link between national and international inequality, which was a topic in the 1970s. Nor is there any mention of social protection, which is high on the agenda of the International Labour Organisation and can make a substantial difference between gross and net inequality. In Western Europe, the difference between ‘pre-tax’ and ‘post-tax’ (including transfers) is no less than 29% in the ratio between the 10% richest and the 50% poorest (Blanchet et al., 2019: 45). Yet social protection is only marginally discussed, without data. Finally, another important point demonstrated by Milanovic and Ravallion: Yes, inequality is bad for growth, but especially the growth of poor people. For the rich, inequality is particularly positive for their economic growth (Vander Weide & Milanovic, 2014; Ravallion, 2001).

- On the need for inequality

The topic of inequality was not a voluntary choice of the international institutions, but they use it to highlight their policy choices: growth, growth and growth for the World Bank and the IMF, and for that they are prepared, if need be, to introduce minimum taxes and allowances. There is no deviation from what was already established in the early 1970s: inequality matters within countries and for reducing it the poor must be able to contribute to growth. Inequality does not require a different policy from that for poverty. A contribution from the higher income groups is not necessary.

The U.N. institutions take a somewhat broader view and also use arguments of social justice. The theme of inequality helps to criticise austerity and poverty policies. The U.N. has a broader development agenda that it wants to highlight. However, all mentions of the old topics of the new world order or peace and international security are gone.

- Inequality, a political topic

What all this confirms is that inequality, much more than poverty, is a political issue that requires ideological choices (Nederveen Pieterse, 2002). Inequality is nowhere problematized. The unequal positions of power are mentioned, but not analysed. The shift from ‘development’ to ‘poverty reduction’, and thus inevitably a shift from countries to people, leads to narrowing the agenda. The link between internal development and international relations disappear.

5.10 A new international agenda?

The UN does point out the importance of multilateral institutions and a global approach, but the measures that are actually proposed only concern inequality within countries. The responsibility of rich countries therefore remains undiscussed.

- What do the numbers say?

If the international institutions fail to provide a neat overview of the available data, this contribution will not be able to do so either.

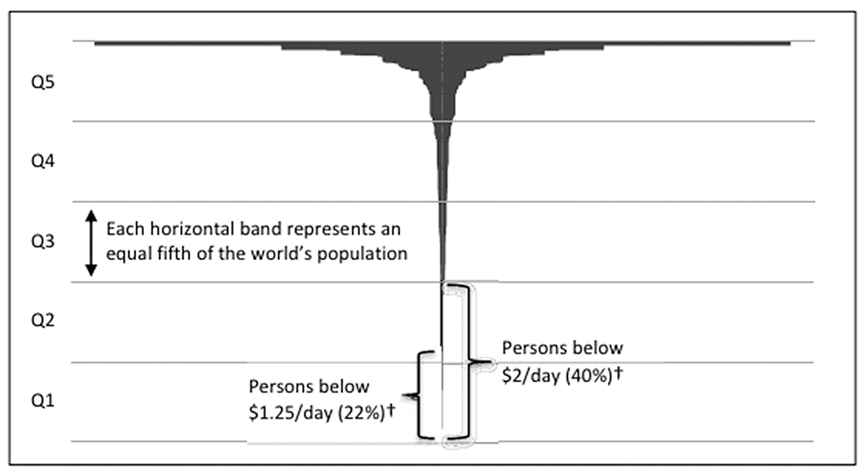

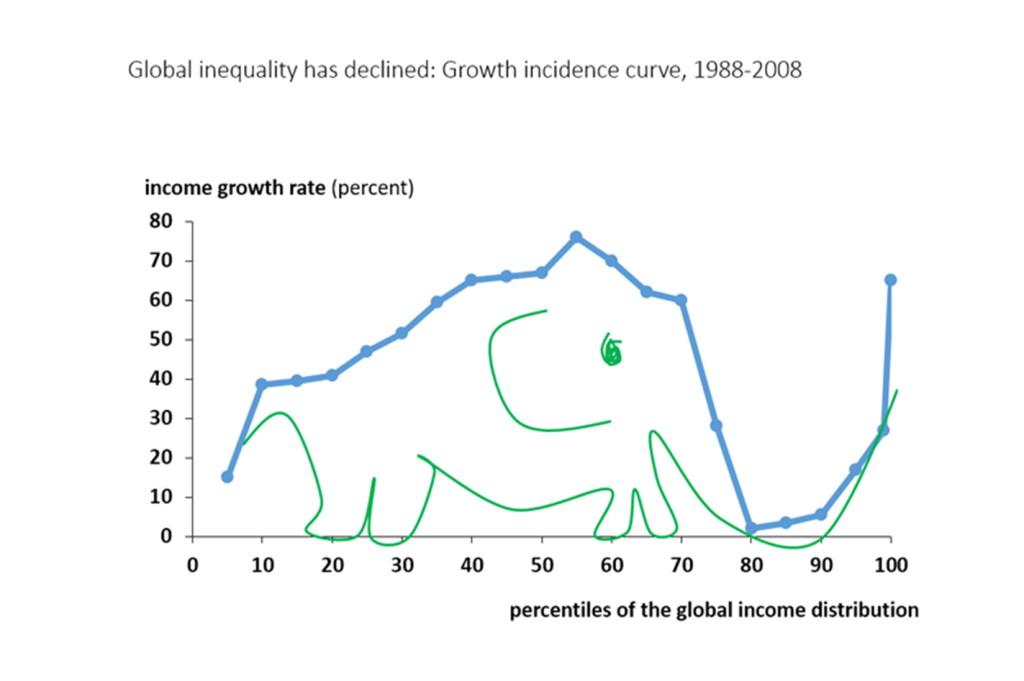

I do want to mention three graphs that need little explanation: 1) the UNDP champagne glass of 1992; 2) the same data ten years later; 3) Milanovic’s famous elephant curve on the impact of globalisation.

- The champagne glass of UNDP

Source: UNDP, 1992

This ‘glass of champagne’ shows that inequality is quite small for a group of up to 60 % of the world’s population. Inequality begins to grow in the fourth group of 20 % and becomes very large in the top group of ‘rich’. At the time, UNDP proposed to replace this glass of champagne by a glass of milk, with a slightly narrower base than the top.

- The glass of champagne overflows

Source: Ortiz & Cummins, 2011: 21

The glass of champagne of 1990 has not become a glass of milk, quite the contrary. Ten years later, inequality has risen to the extent that it is almost entirely in the top 20% richest group, even more so among the 10% richest and is already ‘overflowing’ among the richest 1%.

- The elephant of globalisation

Source: Milanovic, 2016

This elephant shows the effects of almost twenty years of globalisation on income growth, from 1975-1990. The 5% poorest of the world population are the big losers, their income did not increase. The big winners are at the top of the income pyramid (the elephant’s trunk), they are the really rich and the new global middle class (especially in China, India and the rest of Asia). The real income of the top 1% increased by 60%. The other losers are between the percentiles 75 and 90, the upper middle classes of the rich countries. According to Milanovic, this is the biggest shift in income positions since the Industrial Revolution (Milanovic, 2016)

- Thecurrent research boom

For inequality between countries, we can briefly refer to UNCTAD’s classification of the ‘Least Developed Countries’. Initially, in 1971, there were 25 countries with a particularly low national income and level of human development; in 1991, there were 52 and six countries could leave the category by 2021. So 46 countries remain, or almost twice as many as 50 years ago. Which says something about the failures of development policy.

There has been a tremendous amount of research on inequality over the past 20 years (Scheidel, 2017; Stiglitz, 2013; Lansley, 2012; Piketty, 2019 … and many others). It is thanks to this research, by the way, that the topic has also been put on the global agenda, contrary to the poverty theme for which the international institutions took the lead. Because of the many numbers that came to light and the growing indignation associated with it, the international institutions had no choice but to give the issue a place in their own discourse and later also in their policy. In some cases, such as the World Bank, important research has emerged in their own research departments, such as that of Ravallion and Milanovic.

The reports on incomes and assets of a few institutions that have become famous are now followed with great attention: from Oxfam (2022) to CapGemini (2021), Crédit suisse (2021) and Forbes (2021), for some as an indictment, for others from the perspective of asset management.

The most objective data can be found in an academic database created by researchers at the Paris School of Economics: World Inequality Report (Paris; World Inequality Database, 2022), as well as at the World Bank (World Bank).

According to the World Inequality Report, after three decades of globalisation, inequalities are extremely high and can be compared to the peak of Western imperialism at the beginning of the 20st century. The COVID-19 crisis has exacerbated the situation. The data show that the one percent richest have captured some 38% of all additional wealth since the mid-1990s.

The Middle East and North Africa region remains the most unequal in the world. Many countries have become richer, but their governments much poorer. Major inequality remains at the top of the income and wealth scale. Gender inequality is decreasing only very slowly. Environmental inequality is very high both between rich and poor countries and within them (World Inequality Report, 2022).

- Conclusion

How delicate the issue of inequality is for liberal institutions is clear from the risk reports of the World Economic Forum in Davos (WEF, 2014). In 2014, ‘high income disparity’ was number four among the major global risks identified, but the report wastes no further words on it. Inequality is mentioned briefly in almost all WEF reports and one can assume that the topic is also discussed on some of the many panels organised each year, but it is not a major issue. Perhaps because it is not considered a major problem and, in any case, as long as income redistribution remains a taboo subject for these institutions, they do not have solutions for it. There is no room in these institutions for alternative visions of how wealth is produced.

Inequality, as this overview of some global institutions clearly shows, is a political problem with which, unlike poverty, ideological differences cannot be glossed over. One is either prepared to think about redistribution and taxation or one is not. Either we are prepared to put economic growth at risk or we are not. Either we are prepared to curtail the gigantic top incomes or we are not. Either we are prepared to think about alternative visions of development and the economy, or we are not.

Even more than in the implicit discussion between U.N. and Bretton Woods institutions, these differences are clearly reflected in the work of researchers and social movements. What is ultimately at stake is a model of society and the shaping of the future world. For global institutions, this means shaping the development model that can or should be pursued. In all cases, all over the world, wealth is produced collectively, how the results are distributed should therefore be a collective political debate (Piketty, 2021).

If war had not broken out in Europe, there would be some reasons to be optimistic. The debate on climate change is moving forward slowly but undeniably. So is the debate on global taxation, with some first steps on a minimum tax taken in recent years.

Great inequality is by no means a new reality, it is a new problem because Enlightenment thinking prioritised the equality of all people. But as Graeber and Wengrow argue (Graeber & Wengrow, 2021), it is a slippery term, because our societies do not know at all what an equal society should look like. The question of the origin of inequality, they say, is irrelevant. Legal equality is a fiction, which is why great inequality easily comes across as violent. What these researchers do establish is that, even in the distant past, some societies restricted or made inequality impossible, while others did not. This leads them to conclude that we do have a choice, that there is indeed an alternative to the current system. Whether and how much solidarity there is, Piketty also argues (Piketty, 2021), remains a political choice and the subject of social struggle.

Francine Mestrum

Bibliography:

Arndt, H.W. (1987). Economic Development. The History of an Idea. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

Blanchet, T., Chancel, L., Gethin, A. (2019), How Unequal is Europe? Evidence from Distributional National Accounts 1980-2017, WID. World Working Paper 2019/06.

CapGemini (2021). World Wealth Report 2021. CapGemini.

Chenery, H. et al. (1974). Redistribution with Growth. Published for the World Bank and the Institute of Development Studies. London: Oxford University Press.

Cingano, F. (2014). ‘Trends in Income Inequality and its Impact on Economic Growth’, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 163, OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5jxrjncwxv6j-en

Cornia, G.A., Jolly, R. & Stewart, F. (eds). (1987). Adjustment with a Human Face. Protecting the Vulnerable and Promoting Growth. A Study by Unicef. New York: Oxford University Press.

Cornia, G.A. (2004). Inequality, Growth, and poverty in an era of liberalization and globalization, UNU-Wider and UNDP. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Credit Suisse (2021). Global Wealth Report 2021. Geneva: Crédit Suisse.

Does Inequality Matter?”. The Economist, 14 June 2001. Does inequality matter?

Dubet, F. (2022). Tous inégaux, tous singuliers. Repenser la solidarité. Paris: Seuil.

Forbes (2021). Forbes World’s Billionaires List. Forbes Billionaires 2022: The Richest People In The World

Foucault, M. (1972). L’ordre du Discours. Paris: Gallimard.

Graeber, D. & Wengrow, D. (2021). The Dawn of Everything. A New History of Humanity. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Grosh, M. et al. (2022). Revisiting Targeting in Social Assistance. A New Look at Old Dilemmas. Washington: The World Bank.

Holzmann, R. & Jorgensen, S. (1999). Social Protection as Social Risk Management. Social Protection Discussion Paper 9904. Washington: The World Bank

ILO (1952). C102 – Social Security (Minimum Standards) Convention. 1952, No.102)

ILO (1976). Employment, Growth and Basic Needs. Geneva: ILO.

IMF (2017). Fiscal Monitor. Tackling Inequality. Washington: International Monetary Fund.

Kanbur, R. & Lustig, N. (1999). Why is Inequality Back on the Agenda? Paper prepared for the Annual Bank Conference on Development Economics, April 28-30. WP 99-14. New York: Cornell University. (99+) Free PDF Download – Why is inequality back on the agenda | Nora Lustig – Academia.edu

Kapur, D., Lewis, J., Webb, R. (eds) (1997). The World Bank. Its First Half Century. Washington: Brookings Institution Press.

Kidd, S. & Athias, D. (2019). Hit and Miss. An assessment of targeting effectiveness in social protection. Development Pathways. Working Paper March.

Lansley, S. (2012). The Cost of Inequality. London: Gibson Square.

McNamara, R.S. (1972) (1973) Annual Address to the Board of Governors. Washington: The World Bank.

Mestrum, F. (2002). Globalisering en armoede. Over het nut van armoede in de nieuwe wereldorde. Berchem: EPO.

Mestrum, F. (2009). Why we Have to Fight Income Inequality. In: Kohonen, M. and Mestrum, F. (2009). Tax Justice. Putting Global Inequality on the Agenda. London: Pluto Press.

Mestrum, F. (2019). The World Bank and its New Social Contract. The World Bank and its New Social Contract – Global Social Justice

Mestrum (2022). Annex to ‘Global Inequality. Don’t Look Up’, consulted via Global Inequality: Don’t Look Up – Global Social Justice.

Milanovic, B., (2003). Why we all do care about inequality (but are loath to admit it), World Bank Development Research Group. Why We All Do Care About Inequality (But are Loath to Admit it) by Branko Milanovic :: SSRN.

Milanovic, B. (2011). The Haves and the Have-nots, A brief and idiosyncratic history of global inequality, New York: Basic Books.

Milanovic, B. (2016). Global Inequality. A New Approach for the Age of Globalization. Cambridge and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Narayan, D. et al. (2000). Voices of the Poor. Can Anyone Hear Us? New York: Oxford University Press for the World Bank.

Nederveen Pieterse, J. (2002). Global inequality: bringing politics back in, Third World Quarterly, Vol 23, No 6, pp 1023-1046.

Ortiz, I. & Cummins, M. (2011). Global inequality: beyond the bottom billion – a rapid review of income distribution in 141 countries, Social and Economic Policy Working Paper. New York: United Nations Children’s Fund, April 2011, p. 21.

Ortiz, I. and Cummins, M. (2021). Global Austerity Alert. Looming budget cuts in 2021-25 and alternative pathways. Working Paper, Initiative for Policy Dialogue et al.

Oxfam International (2022). Inequality Kills. Oxford: Oxfam GB.

Paris School of Economics. Thomas Piketty – PSE-Ecole d’économie de Paris (parisschoolofeconomics.eu)

Pearson, L.B. (1969). Partners in Development. Report of the Commission on International Development. New York: Praeger Publishers.

Piketty, T. (2019). Capital et Idéologie. Paris: Seuil.

Piketty, T. (2021). Une brève histoire de l’égalité. Paris: Seuil.

Ravallion, M. (2001). Growth, Inequality and Poverty: Looking Beyond Averages, PRWP 2558, Development Research Group, World Bank (multi0page.pdf worldbank.org)

Ravallion, M. (2004). Competing Concepts of Inequality in the Globalization Debate, WB PRWP 3243, March.

Scheidel, W. (2017). The Great Leveler. Violence and the History of Inequality from the stone age to the twenty-first century, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Sen, A.K. (1992). Inequality re-examined. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Stiglitz, J.E. (2013). The Price of Inequality. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

UNDP (1990). Human Development Report 1990. New York: United Nations.

UNDP (2013). Humanity Divided. Confronting Inequality in Developing Countries. New York: United Nations.

UNDP (2019). Human Development Report 2019. Beyond Income, Beyond averages, Beyond Today. Inequalities in Human Development in the 21st Century. New York: United Nations.

UNICEF (1989). The Invisible Adjustment. Poor women and the economic crisis. New York: United Nations.

United Nations (1961). UN Development Decade: a programme for international economic cooperation. A/RES/1710(XVI).

United Nations (1969). Declaration on Social Progress and Development. A/RES/2542(XXIV).

United Nations (1970). Strategy for the second UN Development Decade. A/RES/2626(XXV).

United Nations (1974). Declaration on the Establishment of a new international economic order + Programme of Action. A/RES/3201(S-VI); A/RES/3202(S-VI).

United Nations (1974b). Charter of Economic Rights and Duties of States. A/RES/3281(XXIX).

United Nations (1980). International Development Strategy for the 3rd UN Development Decade. A/RES/35/56.

United Nations (1986). Declaration on the Right to Development. A/RES/41/128.

United Nations (1990). International Development Strategy for the fourth UN Development Decade. A/RES/45/199.

United Nations (1995). Report of the World Summit for Social Development, Copenhagen 6-12 March. A/CONF.166/9.

United Nations (2000). Millennium Declaration. A/RES/55/218.

United Nations (2005). Report on the World Social Situation. The Inequality Predicament. New York, United Nations.

United Nations (2010). Report on the World Social Situation. Re-thinking Poverty. New York: United Nations.

United Nations (2013). Report on the World Social Situation. Inequality Matters. New York: United Nations.

United Nations (2014). Reducing Inequality for Sustainable Development. World Economic and Social Survey. New York: United Nations.

UNRISD (2010). Combating Poverty and Inequality. Structural Change, Social Policy and Politics. Geneva: UNRISD.

Van der Weide, R. & Milanovic, B. (2014). Inequality is Bad for Growth of the Poor (but not for that of the Rich). World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 6963 July.

WBG Strategy (2013). World Bank Group Strategy

WEF Global Risks 2014. Global Risks 2014 – Reports – World Economic Forum (weforum.org)

Wilkinson, R. & Pickett, K. (2010). The Spirit Level: Why Equality is Better for Everyone. London: Penguin.

World Bank (1975). The Assault on World Poverty. Problems of Rural Development, Education and Health. Baltimore and London: The John Hopkins University Press.

World Bank (1990). World Development Report. Poverty. Washington: The World Bank.

World Bank (1993). Poverty Reduction Handbook. Washington: The World Bank.

World Bank (1995). World Development Report. Workers in an Integrating World. Washington: The World Bank.

World Bank (1996). Poverty Reduction and the World Bank. Progress and challenges in the ’90s. Washington: The World Bank.

World Bank (1999), A Proposal for a Comprehensive Development Framework, 21 January 1999. (http://www.worldbank.org/cdf/cdf-text.htm World Bank Document

World Bank (2000). World Development Report 2000/2001. Attacking Poverty. Washington: The World Bank.

World Bank (2005). World Development Report 2006. Equity and Development. Washington: The World Bank.

World Bank (2016) (2018) (2020). Poverty and Shared Prosperity Report. Washington: The World Bank.

World Bank: shared prosperity data: Shared Prosperity: Monitoring Inclusive Growth (worldbank.org)

World Inequality Database. Home – WID – World Inequality Database

World Inequality Report (2022). World Inequality Report 2022 – WID – World Inequality Database

Leave a Reply